Claire Hemingway in ‘The Conversation’: Cultivating for color: The hidden trade-offs between garden aesthetics and pollinator preferences

Cultivating for color: The hidden trade-offs between garden aesthetics and pollinator preferences

People often prioritize aesthetics when choosing plants for their gardens. They may pick flowers based on colors that create visually appealing combinations and varieties that have bigger and brighter displays or more fragrant and pleasant-smelling flowers. Some may also choose species that bloom at different times in order to maintain a colorful display throughout the growing season.

Many gardeners also strive for ecological harmony, seeking to maintain pollinator-friendly gardens that support bees, butterflies, hummingbirds and other pollinators. But there are some notable ways in which the preferences of humans and pollinators have the potential to diverge, with negative consequences for pollinators.

As a cognitive ecologist who studies animal decision-making, I find that understanding how pollinators learn about and choose between flowers can add a helpful perspective to garden aesthetics.

Pollinator preferences and rewards

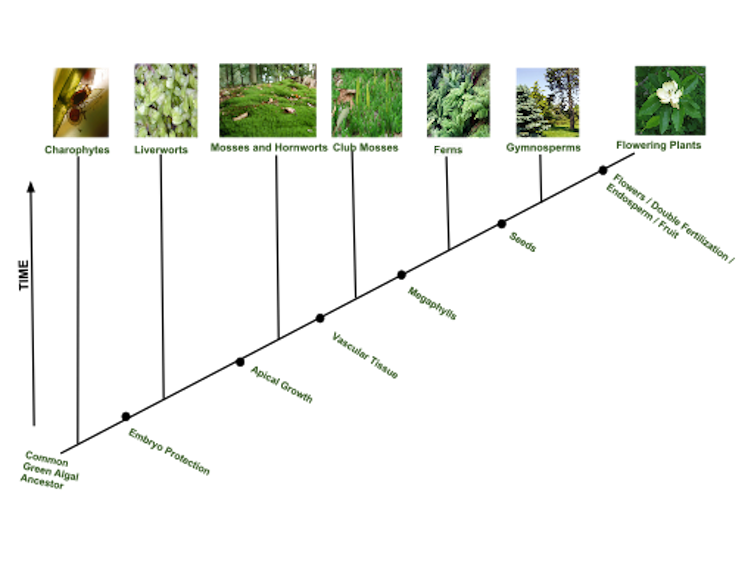

Over millions of years, plants have evolved suites of floral traits to attract specific types of pollinators.

Pollinators can be attracted to flowers based on color, pattern, scent and texture. For instance, hummingbirds typically visit bright red and orange flowers with narrow openings and a tubular shape. The striking red cardinal flower is one that is primarily pollinated by hummingbirds, for example.

Bees are often attracted to blue, yellow and white flowers that can be either narrow and tubular or open. Lavender, sage and sunflower plants all bear flowers that attract bee pollinators.

Flowers offer rewards to visiting pollinators. Nectar is a sugar-rich solution that flowers produce to attract pollinators, which use it to meet their energy needs.

Flowers have an ulterior motive for providing this energy source. While drinking the nectar, pollen can get stuck on the pollinator and transferred to the next flower it visits. This process is essential for the plant’s reproductive success. Pollen contains the plants’ male gametes, which, when deposited onto another flower in the right place, can fertilize the female gametes and produce seeds that grow into new plants. Pollen is also nutrient-rich, containing proteins, lipids and amino acids. Many species, such as bees, collect pollen to feed their developing young.

A battle for resources

Pollinators visit flowers in search of floral rewards. But modifying the features of flowers for aesthetics can be a hindrance to pollinators trying to get these rewards. For example, popular garden plants such as roses and peonies are often bred to have more petals and larger flower heads, making them more visually striking and appealing to humans. But these extra petals may block a pollinator’s access to the center of the flower, where floral rewards are located.

Further, plants have limited resources. Spending them on building aesthetically pleasing but energetically expensive features can mean there’s less left to invest in signals and rewards essential for attracting pollinators. In extreme cases, breeding for aesthetics has led to plants with what scientists and gardeners call “double flowers.” In these varieties, extra petals replace reproductive parts entirely. These plants are often altogether unrewarding for pollinators, since the flowers no longer produce nectar or pollen. Double flowers occur from mutations that convert the pollen-producing stamens and other reproductive organs into petals. They can occur naturally but are rare in wild populations.

Since these double flowers cannot spread pollen or produce seeds effectively, they are unable to reproduce in the wild and pass these mutations on. To cultivate them as garden varieties, people propagate these plants through cuttings – small sections cut from the stem that can be rooted to grow clones of the parent plant. Many common garden plants have popular double-flowered varieties, including roses, peonies, camellias, marigolds, tulips, dahlias and chrysanthemums.

Roses, for example, have become synonymous with having many densely-packed petals. But these popular garden varieties are usually double-flowered or have many extra petals blocking access to the center of the rose and provide no rewards to pollinators.

Consider making your gardens friendlier to pollinators by avoiding these double-flowered plants, and ask your local garden center for recommended varieties if you need help.

Sometimes gardeners intentionally prevent plants from flowering, which limits or eliminates their value to pollinators.

For example, herbs such as thyme, oregano, mint and basil are generally most flavorful and tender before the plant begins to flower. Once it flowers, the plant diverts energy to reproductive structures, and leaves become tougher and lose flavor. As a result, gardeners often pinch off flower buds and harvest leaves frequently to promote continued growth and delay flowering. Letting some of your herbs flower occasionally can help pollinators without affecting your kitchen supplies too much.

Finding the right flowers

Flowers with unusual colors and stronger fragrances can be difficult for pollinators to detect and recognize.

People might favor bright and unusual flower colors in their gardens over naturally occurring shades. But this preference might not align with what the pollinators have evolved to favor in nature. For example, planting human-preferred colors, such as white or pink morphs of hummingbird-pollinated flowers that are typically red, can reduce a flower’s visibility and attractiveness. Even when cultivated varieties have a similar enough color to natural ones to attract pollinators, they may lack other important visual components, such as ultraviolet floral patterns that can guide pollinators to nectar sources.

Breeding plant varieties to accentuate particular aesthetic traits may have unintended consequences for other traits. Changes in flower color through selective breeding can also affect leaf color, as genes involved in pigment production can affect multiple plant tissues. Besides changing the overall appearance of the plant, changing leaf color may alter background contrast between flowers and the leaves, which can make flowers less conspicuous to pollinators.

Many pollinators use a combination of color and scent to detect and discriminate between flowers. But breeding for traits such as color and brightness can alter floral scents due to unintended genetic changes or energetic trade-offs.

Scent helps pollinators locate flowers from farther distances, so unfamiliar or reduced fragrance may make flowers harder to find in the first place. Disruption in either color or scent can make flowers less noticeable to pollinators expecting a familiar pairing and can hinder a pollinator’s ability to learn which flowers are suitable for them in the first place.

A balanced approach for healthy gardens

When flowers are harder to find, pollinators are less likely to visit them. When they offer poor or no rewards, pollinators quickly abandon them for better options. This disruption in plant-pollinator interactions has implications not only for pollinator health but also for garden vitality. Many plants rely on animal pollinators to reproduce and make mature seeds. These are either collected by gardeners or allowed to drop to the ground and sprout on their own to grow new flowering plants the following year.

When selecting plants for a garden, gardeners who want to support pollinators might consider choosing native varieties that have evolved alongside local pollinators.

In most areas of the country, there are native plants with colorful and interesting flowers that bloom at different times, from early spring to late fall. These plants tend to produce reliable floral signals and offer the nectar and pollen needed to support pollinator nutrition and development.

Sterile varieties and double flowers offer little or no rewards for pollinators, and gardens with them may not attract as many pollinators. Letting herbs flower after some harvesting is another simple way to support beneficial insects.

With choices informed by not just your aesthetic preferences but also those of pollinators, you can create colorful gardens that support wildlife and stay in bloom across various seasons.

Claire Therese Hemingway, Assistant Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.